On a quiet corner in Tremé, in New Orleans, there stands an old brick building. White doors and teal green window panels signal to guests that comfort is indoors. For those who know what they’re walking into, there’s history inside of those doors, too.

Dooky Chase isn’t just a restaurant; it’s a New Orleans institution. The site of Civil Rights organizing, Creole cuisine preservation, and the work site of one of the most important chefs in American history, walking into Dooky Chase is walking into one of the most significant buildings in the southern region of the United States.

Leah Chase, a stalwart in southern food, was a storyteller, art collector, activist, and chef. Born in 1923 and brought up in the center of Louisianan cuisine, Chase used her life to preserve and innovate Creole cuisine, to play an integral role during the Civil Rights movement, and to share the story and significance of Black women in food through her restaurant. Chase’s restaurant, opened in 1941 and named after her husband, Edgar “Dooky” Chase II, was the only upscale restaurant in the New Orleans area that served Black patrons ahead of desegregation. Chase was skilled in her culinary profession, and was known to offer some of the best gumbo and fried chicken in the city. Her shrimp Clemenceau, a dish of generously seasoned shrimp, mushrooms, peas, and potatoes, served in a shallow bath of lemon butter sauce, was one of the most recognized dishes at the restaurant, and throughout the south. The Chases were deeply involved in civil rights activism, and would host voter registration organizers at the restaurant. They also hosted members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), local activists, the Freedom Riders, and regularly cooked for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The site was a safe haven for organizing, and several bus boycotts were organized right in the restaurant, often over a bowl of gumbo or plates of fried chicken. The restaurant’s upstairs room was known as a “secret” meeting place, and while local officials came to know of these supposed “illegal” meetings, the restaurant was so popular that law enforcement’s hands were tied: to shut down the restaurant would be to incur the wrath of the public.

“Chase was skilled in her culinary profession, and was known to offer some of the best gumbo and fried chicken in the city.”

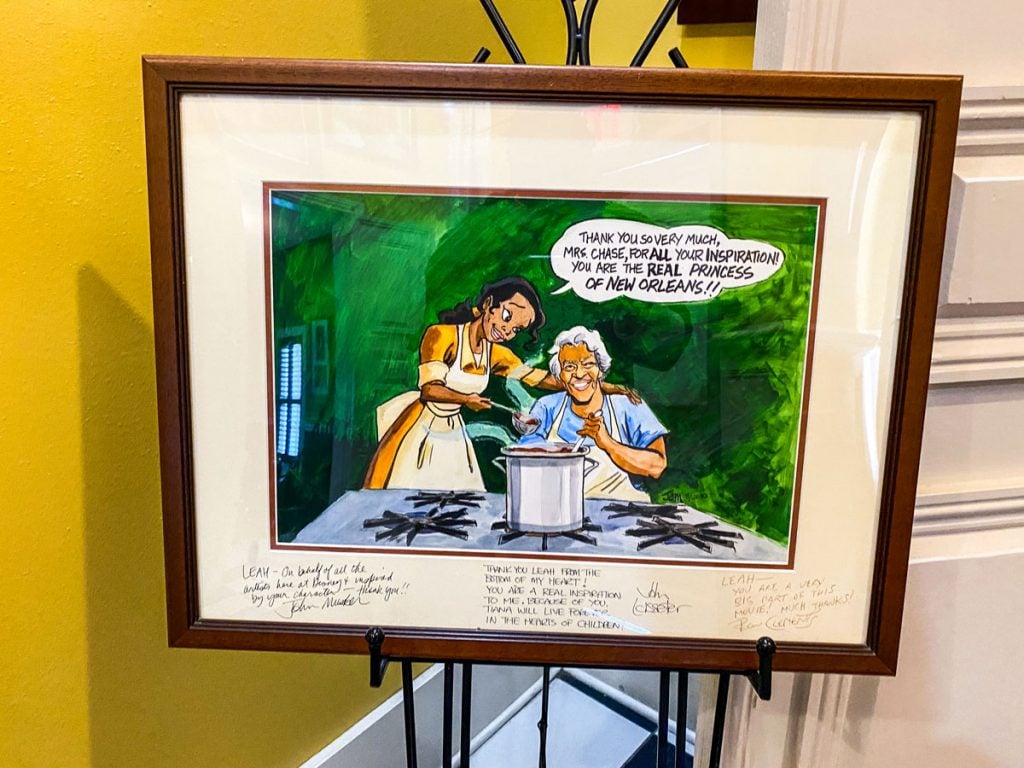

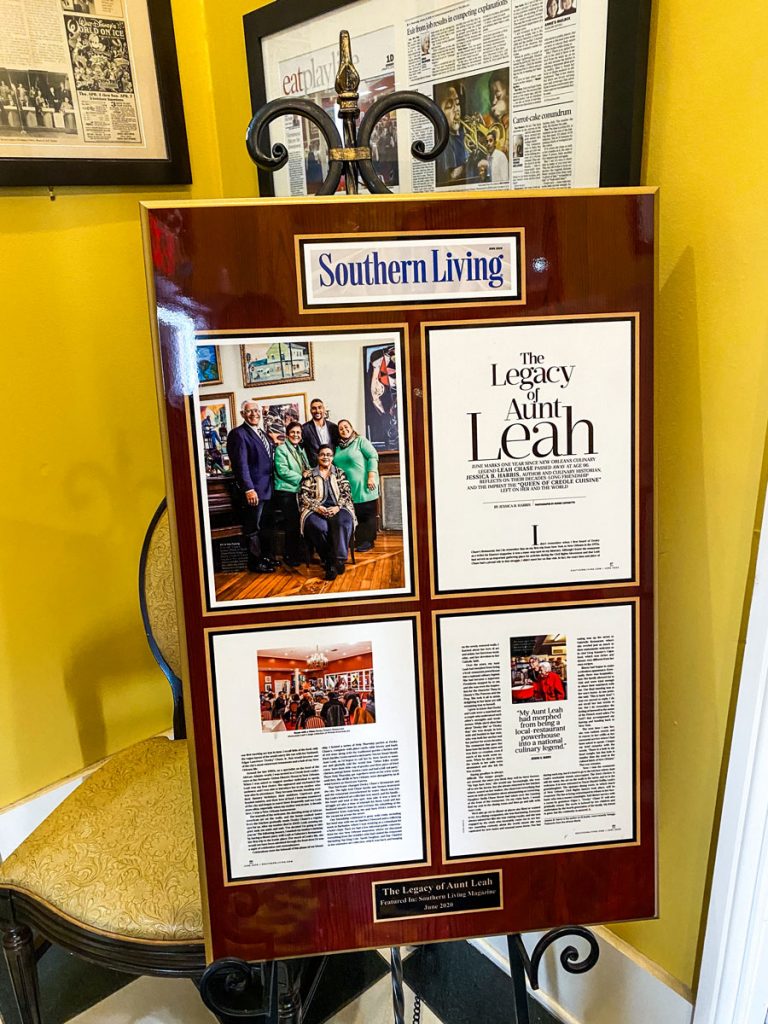

Chase’s life and legacy are well-known across the food world, and even outside of food. Chase was the inspiration for Disney’s first Black princess, Tiana, in “The Princess and the Frog.” President Obama visited the storied building to meet Chase, and numerous other politicians, actors, leaders, and civilians stopped by the restaurant to get a chance to meet Chase, up until she passed in 2019. Her accolades make up pages of text, and the reverence for her work is apparent throughout New Orleans. Her children have carried on her legacy, allowing those of us who didn’t get a chance to visit during her lifetime, to still be able to enjoy the fruits of her labor.

Visiting Dooky Chase during a trip to New Orleans is essential. As you walk into the building, you feel as if you’ve been hit with a gust of the past. There’s pride, joy, and history in the building that can be felt immediately upon stepping through the doors. Ahead of walking into the dining room of red walls, visitors are greeted by newspaper articles from Southern Living, The New York Times, and others; there are pictures of Chase smiling and laughing with presidents Obama and Bush; there’s a thank you gift from Disney–a mesmerizing photo of an animated Ms. Chase with Princess Tiana, a character that would carry on her legacy for future generations of kids.

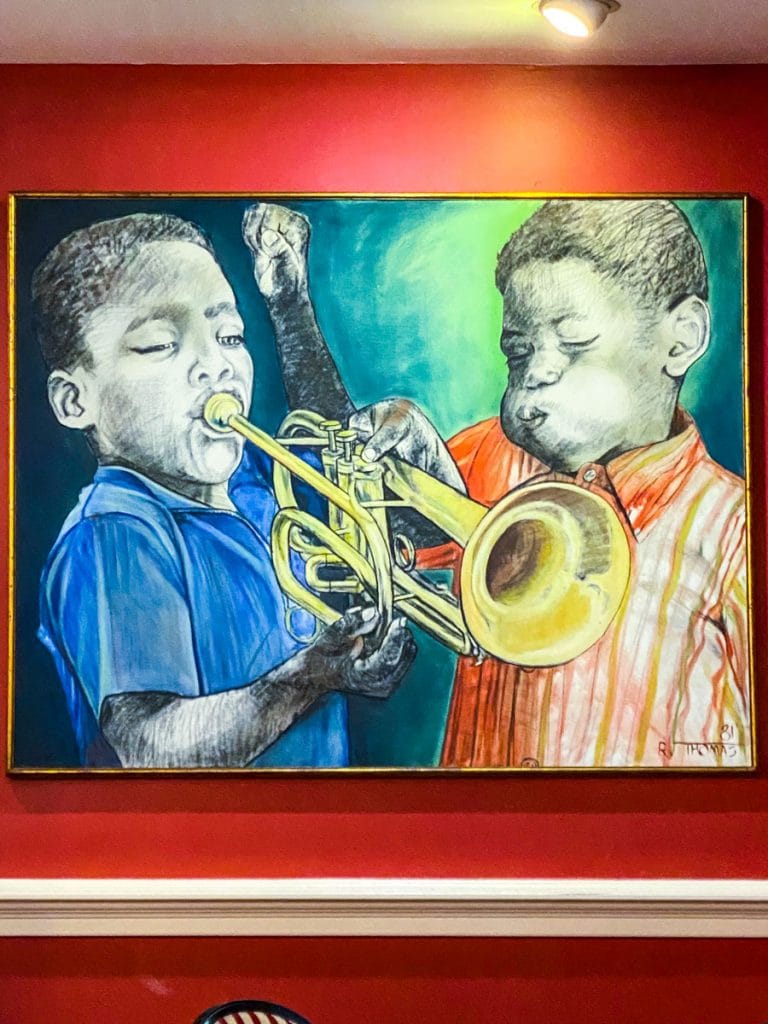

Indoors, guests are greeted with the legendary red walls, covered in art that Chase had collected throughout her life. The cover of her cookbook, the Dooky Chase Cookbook, was visible, and artwork of Black people enjoying jazz and the wonders of life painted the walls. Over the speakers during the wintertime, holiday jazz played, and “The Christmas Song” and “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” sounded cooler than ever before. Sitting down, you can take it all in. At Dooky Chase, it’s more than just food at the table; diners can get a glimpse of the past, and see how one person’s work in the kitchen would generations to come.

When I visited the restaurant, I couldn’t resist doubling up–I ordered Chase’s shrimp etouffee, and her famous shrimp Clemenceau, the first time I’d ordered the dish. The shrimp Clemenceau, served so hot that the steam blanketed my camera when I tried to take a picture, was unlike anything I’d tasted. Creole in its roots, sure, but a clear example of Chase’s aptitude for creativity and culinary flair. The perfectly seasoned dish filled me easily, to the point where I could only enjoy a few bites of the shrimp etouffee. My oddly small appetite for the day proved frustrating, because I wanted to devour both dishes immediately.

Deciding not to let gluttony take over, I sipped a glass of white wine while my waiter boxed my food. Glancing around, I recognized a dining room filled with people entirely different from those who likely graced the room sixty years early. As I paid and grabbed by order, I realized that Chase’s legacy would go far beyond what any of us had enjoyed in the room that day. Her life, and her impact would stick with New Orleans, and stick with us all. We are truly lucky for it.

Dooky Chase isn’t the only restaurant with a storied Civil Rights history. Across the country, travelers can enjoy some of the same restaurants that fed activists and citizens during the Civil Rights Movement, and beyond.

“Her life, and her impact would stick with New Orleans, and stick with us all. We are truly lucky for it.”

The Four Way

998 Mississippi Blvd

Memphis, TN 38126

Opened by couple Irene and Clint Cleaves in 1946, the Four Way was one of the few dining institutions in the south where Black and white customers dined together. A Memphis institution, the restaurant was initially just a tiny counter in a pool hall with a nearby barber shop, and eventually transformed into the full dining room that’s visible today. It was a favorite of Dr. Martin Luther King’s, and the Civil Rights leader would stop by whenever he was in town. Many activist meetings were held over classic southern dishes like fried fish, fried catfish, and peach cobbler. Though the ownership and menu has changed over time, the essence of the menu has remained the same: full southern and soulful. Dishes like fried catfish, neckbones, sweet potatoes, collard greens, and cornbread serve as the foundation for meals that remind guests of being back home in an aunt’s house.

Paschal’s

180 Northside Dr SW

Atlanta, GA 30313

There’s a seemingly endless amount of history in the storied city of Atlanta. Paschal’s, a restaurant located within the Historic Castleberry Hill Neighborhood, is demonstrative of the rich and flavorful history that embodies that city. Opened in 1947 by brothers James and Robert Paschal, the first location of the restaurant on West Hunter Street opted to focus on making fried chicken the house specialty. With that, a “secret recipe” emerged, making Paschal’s fried chicken some of the most recognized and revered in the region. The original location was another favorite of Dr. King, who was born and raised in Atlanta, and served as a meeting place for notable leaders and entertainers like Maynard Jackson, Aretha Franklin, and Vice President Al Gore. From providing catering services to financially supporting protesters during the Civil Rights Movement, Paschal’s turned opted for a restaurant model that equalized good food and community service. Today, Paschal’s may be in a different location, but the legendary flavors shine through its many offerings, like it’s southern fried green tomatoes touched with a layer of Cajun ranch dipping sauce, it’s slow-smoked pulled pork, their jumbo fried shrimp, and their myriad of sides, like green beans, mashed potatoes with gravy, and macaroni and cheese.

Lannie’s Bar-B-Q Spot

2115 Minter Ave

Selma, AL 3670

Nestled in the small town of Selma, Alabama, Lannie’s Bar-B-Q Spot is sometimes overshadowed by the town’s more painful history. Yet, Lannie’s Bar-B-Q played an integral role in that very history, and helped move Selma from a hotbed of racial inequity to the southern town it is today. Opened in 1942 with a dirt floor, the family owned spot became known for their culinary aptitude for barbecuing hogs. Located in the Black Belt, Black Americans in the area lived below the poverty line and weren’t allowed to vote. Lannie’s provided a place where organizers could strategize on how to build better, stronger, more equitable communities, and enjoy some exceptional potato salad while doing so. When Bloody Sunday occurred, an organized protest that saw hundreds of protestors brutally beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, news spread that Dr. King was coming to town. Lannie’s became known for sharing their comforting barbecue sandwiches with protestors, ensuring that everyone had enough to eat to get through the hard times.

Though the town has lost a sizable amount of its population, the restaurant has held on. Unassuming and remaining true to its humble roots, patrons can enjoy dishes like rib sandwiched, catfish filets and whiting, corn nuggets, and fried okra, usually served on a styrofoam plate or in a to-go back. What’s not visible in interior style shows up in flavor–each bite is a delightful, comforting ode to the south.

“Lannie’s Bar-B-Q played an integral role in that very history, and helped move Selma from a hotbed of racial inequity to the southern town it is today.”

Big Apple Inn

509 N Farish St

Jackson, MS 39202

What may be small in size can contain multitudes, or so is the case at Misssissipi’s Big Apple Inn. Home to the pig ear sandwich, a slider bun containing pig ear cooked in a pressure cooker, sandwiched within mustard, slaw, and homemade hot sauce, the institution holds a lot of bragging rights. It holds a lot of history, too. Opened in 1952 by Mexican-American immigrant Juan “Big John” Mora, the restaurant became a hub for various American staples, like hamburgers, bologna sandwiches, and “smokes,” or buns filled with ground smoked hot sausage. Just above the hole-in-the-wall restaurant, the rooms above, located on Farish Street, were used and occupied by Civil Rights leaders like Medgar Evans and Fannie Lou Hamer. The area is home to history that extends through the Civil Rights movement and beyond. Located in a once-thriving Black neighborhood that was nicknamed “Little Harlem.” leaders and activists met at the restaurant to discuss protest strategy and desegregation tactics, including the 1961 Freedom Rides. Current owner Geno Lee is adamant about keeping the restaurant in business. Though business is tough at times, people still file into the restaurant to get a variety of dishes, like the hot sausage sandwich, hot dog slider, tamales, and of course, the pig-ear sandwich.

Sylvia’s

328 Malcolm X Blvd

New York, NY 10027

Much of Civil Rights history is told through the lens of the south. It makes sense–that’s where Jim Crow laws were enacted, and where most Black Americans lived up to the 20th century. Many African Americans, however, sought refuge in regions they believed to be less violent. Large towns in the north saw huge waves of migration from the south, which became known as “The Great Migration.” Black Americans established towns and neighborhoods that would become cultural enclaves, one of the most important being Harlem.

In Harlem, many African American families who moved from the south developed cultural centers like churches, community centers, and of course, restaurants, that would allow them to remain connected to their culture. Syvlia’s is one such place. Opened in 1962 by Sylvia Woods, a woman known as “The Queen of Soul Food,” Sylvia’s provided unique dining experiences that resembled those of the south. Gospel brunch Sundays are a regular event, and the restaurant has attracted the likes of Nelson Mandela, Whoopie Goldberg, and Barack Obama. The food reflects that of Southern soul food. Golden fried shrimp, bbq short ribs or beef, stewed turkey wings, and southern-style chitterlings all speak to the comforting, southern nature of the restaurant’s offerings. Sides like potato salad, candied yams, grits, and black-eyed peas demonstrate that while soul food isn’t monolithic, there are some key calling cards that can comfort those far away from home.

Related Articles

-

Travel & Culture March 16, 2020 | 6 min read Significance of Sustenance: Burlington I grew up in the shadow of the slopes in the Pocono Mountains, but the icy Pennsylvania conditions made skiing decidedly unfun for fall-prone little-ol’ me.

Travel & Culture March 16, 2020 | 6 min read Significance of Sustenance: Burlington I grew up in the shadow of the slopes in the Pocono Mountains, but the icy Pennsylvania conditions made skiing decidedly unfun for fall-prone little-ol’ me. -

Travel & Culture April 02, 2020 | 8 min read A Brooklyn Pizzeria Fights Through COVID-19 COVID-19 hit the city like a slow-moving hurricane. We knew it was coming, but we were still in shock. Everything was uncertain.

Travel & Culture April 02, 2020 | 8 min read A Brooklyn Pizzeria Fights Through COVID-19 COVID-19 hit the city like a slow-moving hurricane. We knew it was coming, but we were still in shock. Everything was uncertain. -

Travel & Culture June 23, 2020 | 6 min read Distinctive Process: Maori Hangi Steaming geothermal pools set against a vivid blue sky, in the middle of lush natural surroundings and a day spent soaking up indigenous Maori culture.

Travel & Culture June 23, 2020 | 6 min read Distinctive Process: Maori Hangi Steaming geothermal pools set against a vivid blue sky, in the middle of lush natural surroundings and a day spent soaking up indigenous Maori culture.